Our nationwide focus in K-12 education is on preparing students with the knowledge base and skills for higher education and the professional workplace. This focus is particularly relevant when it comes to communication and literacy. Teachers serving English learners, struggling readers, and youth from under-resourced households play a pivotal role in advancing their students’ verbal and written command of advanced social and academic English. To develop the verbal skills of synthesis, interpretation, explanation and argumentation, under-prepared scholars require explicit, interactive instruction across the curriculum, as well as teachers who serve as eloquent, unswerving models of the language of academic achievement. If one thing has become clear in all my work over the past 25 years to improve lesson engagement and learning for English learners and basic readers, it is that we need to enlist teachers as language mentors who approach lesson design and delivery with efforts to expose, enrich, and equip students linguistically.

Over the past three years, I have written a number of feature articles for Language Magazine, detailing ways in which K-12 educators can equip their students with the language knowledge required for young scholars to be able to read and respond to complex texts, engage in collaboration, and construct competent responses. Following is an excerpt from the article series launch. You can read the entire article, here.

Launching an Academic Register Campaign

As purveyors of the language of school, teachers across the K-12 spectrum must assume responsibility for exposing their students to the most articulate and imitable variety of English that will advance their command of academic register. Serving as a viable academic language mentor begins with comprehending and successfully communicating the meaning of register. A register is “the constellation of lexical (vocabulary) and grammatical features that characterizes particular uses of language (Schleppegrell, 2001). In layman’s terms, a register is the word choices, sentence types, and grammar used by speakers and writers in a particular context or for a particular type of presentation or writing. In student-friendly terms, a register is the way we use words and sentences to speak and write in different situations or for different reasons.

Introducing the term register to K-12 students at any age with accessible examples helps to concretize a potentially alien concept. This digitally-savvy generation of secondary school students fairly readily grasps the differences between the language one hastily scribes to send a text message to a friend or family member (abbreviated quotidian words and phrases, incomplete sentences, emoticons) and the more formal tone, complete sentences, and precise vocabulary one deploys in an e-mail message to a strict teacher attempting to communicate a viable excuse for turning in a late high-stakes assignment. Elementary school students easily comprehend the distinctions in the ways we would ask a grandparent, minister, or principal for assistance as opposed to how we might ask a sibling or close friend. Young language scholars in every grade tend to immediately relate to analogies with formal and casual clothing choices. They recognize the inappropriateness of appearing at a family wedding, church service, or formal dance attired in clothing more suitable for weekend chores or playing outside after school with neighborhood friends.

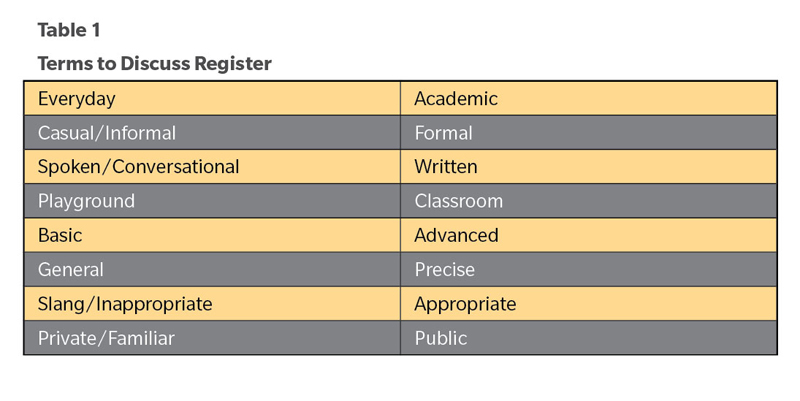

Discussions of register with students should be at once direct, nonjudgmental and respectful. At no point should an educator ever imply that home use of language is anything less than appropriate. In fact, the term “home language” is best left out of this candid conversation altogether. Students need to rest assured that having an agile command of “everyday English” is absolutely imperative if they wish to have friends and intimate relationships. It is the rare individual who prefers to interact regularly with someone who only utilizes formal academic English. Further, “everyday English” varies from one community to another and moving fluidly within home and school environments warrants being sensitive to language uses in different contexts. Clarifying register distinctions with developmentally-appropriate contrasting terms helps learners at successive language proficiency and age levels continue to grapple with this essential linguistic concept (See Table 1).

Eliciting Academic Responses from Under-prepared Students

After introducing the notion of register, an academic language mentor should clarify for students the essentials of constructing an appropriate academic response. My experiences teaching first-generation college freshmen and adolescent English learners have made me keenly aware of the fact that most have progressed in their schooling perplexed by a teacher’s admonition to “respond in a complete sentence.” Consider this commonplace scenario. A social studies teacher poses a discussion question to activate and build background knowledge prior to assigning a chapter on recent U.S. immigration: What are common challenges faced by recent U.S. immigrants? After allowing adequate wait time for individual reflection, the teacher asks a mixed-ability class comprised of native English speakers and English learners “Would anyone like to share?” When no one immediately steps up to the plate to offer a voluntary contribution, the teacher calls on students randomly. Typical responses include “English,” ”New foods,” and ”Finding a job.” Probed to rephrase an example in a complete sentence, a flummoxed contributor replies inaudibly “It’s learning English.”

Despite our earnest efforts to elicit detailed and audible responses, few under-prepared students have figured out what we actually mean by “answer in a complete sentence.” What teachers across the disciplines anticipate is a complex statement incorporating precise vocabulary from the assigned question, for example, “One common challenge faced by many recent immigrants is learning an entirely different language.” On the first day of my English language development classes, I demystify this process for students while establishing my expectations for active, responsible participation in unified-class and collaborative discussions. I visibly display questions and appropriate complete responses as illustrated (in the table) below. The inevitable question arises: “Why didn’t my teachers show me how to do this years ago?” We simply can’t expect our students from diverse socio-economic and linguistic backgrounds to be armchair applied linguists, capable of successfully deconstructing the nuances of school-based language.

###

This article originally appeared in Language Magazine - the journal of communication and education. Click here for more articles on language and college-and-career readiness.

Kate Kinsella, Ed.D. develops custom coursework for employed K-12 educators in San Francisco State University’s Center for Teacher Efficacy. She provides consultancy to state departments of education throughout the U.S., school districts and publishers on evidence-based instructional principles and practices to accelerate academic English acquisition for language minority youths. Her professional development institutes, publications and instructional programs focus on career and college readiness for English learners, with an emphasis on high-utility vocabulary development, informational text reading and writing.

References

August, D., & Shanahan, T. (Eds.). (2006). Developing literacy in second language learners: Report of the national literacy panel on language-minority children and youth. Center for Applied Linguistics.

Dutro, S., & Kinsella, K. (2010). English language development: Issues and implementation in grades 6-12. In Improving education for English learners: Research-based approaches. California Department of Education.

Kinsella, K. (Oct. 2012). Disrupting discourse. Language Magazine, 18-23.

Schleppegrell, M.J. (2001). Linguistic features of the language of schooling. Linguistics and education. 12(4): 431-459.